Now Reading: USA Intervencionism: The Americas Prepare For The Impact of the Trump Era 2.0

-

01

USA Intervencionism: The Americas Prepare For The Impact of the Trump Era 2.0

USA Intervencionism: The Americas Prepare For The Impact of the Trump Era 2.0

With less than 50 days into his 1,461-day term, President Trump is determined to expand the influence of the United States in the Americas. He believes he has both the mandate and the raw military and economic power to reshape the hemisphere on his own. Instead of distinguishing between allies and enemies or between democrats and autocrats, the Trump administration divides the world into the strong and the weak.

Trump is echoing Thucydides, who, speaking about Athenian imperialism, observed that “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.” And while he undoubtedly manages to impose his will on some countries in the short term, the long-term consequences may end up contradicting his own interests.

Threat of a Trade War

In the first weeks of his administration, Trump and his team implemented a series of protectionist measures that caused global markets to plummet in the US, Europe, and Asia. On March 4, his government imposed a 25% tariff on all imports from Canada and Mexico, in addition to a 20% tariff on Chinese products. These measures triggered a swift retaliation from Canada and China.

The next day, with stocks in sharp decline, Trump temporarily suspended most tariffs until April. Canada, however, maintained some of its reciprocal tariffs, amid growing fears of a prolonged trade war with significant global consequences. The tariffs, which are sometimes applied and sometimes suspended, not only sow confusion in the markets, but also threaten to slow growth, drive inflation, and cost workers their jobs.

A More Interventionist US

Trump’s aggressive threats not only reinforce his “America First” foreign policy but also signal a broader foreign policy of “Americas First.” This strategy harks back to the doctrines of the 19th and early 20th centuries, advocated by former presidents such as Monroe, Polk, McKinley, Jackson, Roosevelt, and Wilson, all proponents of US primacy in the Western Hemisphere.

The current administration’s focus on curbing drug trafficking, restricting immigration, and correcting trade imbalances—real or perceived—has resulted in interventionist rhetoric with historical precedents. While Trump’s emphasis on regional influence represents a break from the US disengagement throughout the 21st century, it also revives concerns about the history of US interference in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The appointment of Cuban-American Marco Rubio as Secretary of State signals the Trump administration’s growing interest in Latin America and the Caribbean. Last month, Rubio embarked on his first diplomatic tour, visiting Panama, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and the Dominican Republic—a historic feat for a US Secretary of State.

He is supported by several senior Trump administration officials with interests and connections in the region, including Deputy Secretary of State Chris Landau, National Security Advisor Mike Waltz, and former Senior Director of the National Security Council for Western Hemisphere Affairs, Mauricio Claver-Carone. This renewed focus on Latin America reflects the US government’s desire to reassert its regional influence, even if it comes at the expense of traditional alliances in the region.

The Americas Under Threat

Canada, historically considered the closest ally of the United States, now finds itself in strong disagreement with its neighbor due to the ongoing threat of new tariffs. These measures are having a significant impact on supply chains shared by the two countries, affecting sectors ranging from manufacturing to agriculture.

The shift in US stance has sparked debates in Canada about the need to reduce its dependence on the US, including the diversification of trade partnerships, especially with the European Union (EU). The country’s largest pension fund is reportedly analyzing alternatives to reduce its exposure to the North American market.

Trump’s actions have not only destabilized the Canadian electoral race in favor of the Liberal Party but have also united Canadians, accelerating measures to reduce federal and interprovincial trade barriers and triggering consumer boycotts, including boycotts of US products.

Meanwhile, countries in Central America and the Caribbean are dealing with the consequences of changes in diplomatic relations, increased competition, intensified deportations, and reduced US assistance. While the tariffs imposed by Trump are expected to exacerbate labor shortages and raise production costs in the United States, they may also reduce remittance flows, a crucial factor for local economies.

The US government’s tough stance on border security and immigration has raised concerns about potential destabilization. And while Trump’s actions risk increasing resentment and political turbulence, they have yet to provoke mass protests or calls for regional solidarity, as has happened in the past.

Empowering the Far Right

At the same time, the political landscape in Latin America is undergoing transformations, with far-right ideologies gaining strength as the left disintegrates in many regions. Figures like Javier Milei in Argentina and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador have adopted a populist rhetoric similar to Trumpism (and its corresponding anti-wokeism), reflecting a broader regional shift toward conservatism.

These trends, combined with aggressive crackdowns on organized crime (and the reduction of US efforts to combat corruption), raise troubling questions about the future of democratic norms and human rights in these countries. Additionally, the designation of several cartels and gangs as “terrorists” by the US government has sparked fears in Mexico and other countries in the region about possible violations of sovereignty.

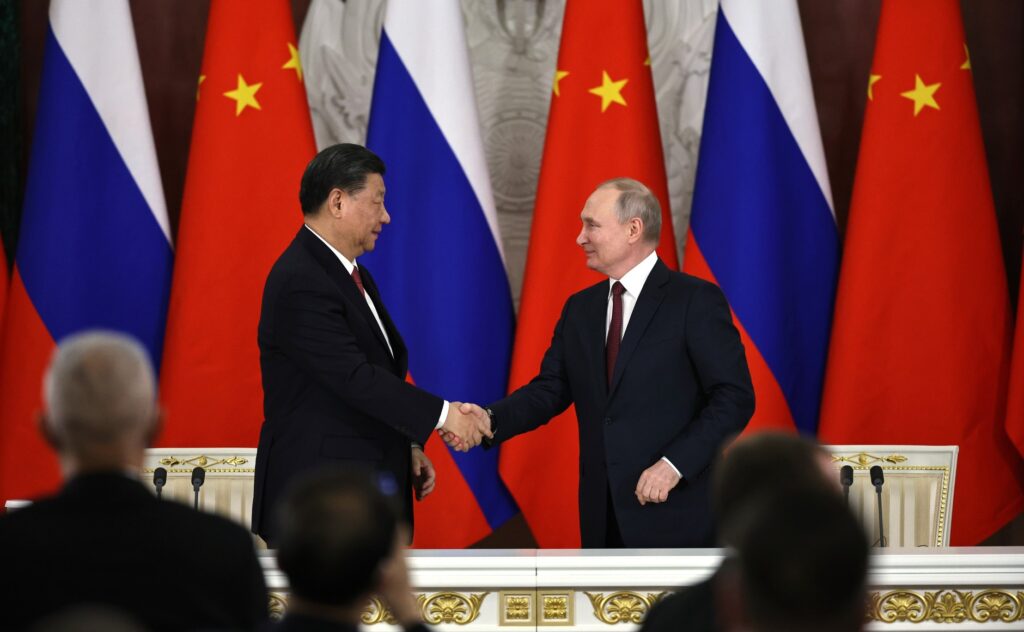

The China Factor

China’s strong influence in Latin America adds another layer of complexity to the US strategy. As Latin America’s main trading partner, China’s presence challenges US efforts to reassert its hegemony.

The administration’s attempts to curb this influence involve pressuring countries to reduce their dependence on China, but this strategy may generate resentment and, paradoxically, bring these nations even closer to Beijing—even at a time of political, economic, and demographic challenges within China itself.

After Marco Rubio demanded “immediate changes” from Panama regarding China’s “influence and control” over the canal, a Hong Kong-based company agreed to sell its stake in two strategic ports to a group led by the US investment bank BlackRock. Meanwhile, the deepening of US ties with Russia could reshape alliances in the region, raising further questions about how Washington will deal with adversaries like Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

Expansionist Ambitions

Trump 2.0 has ushered in a period of greater US involvement in the Americas, marked by protectionist policies, aggressive deportation measures, and a reassertion of influence. Rightly or wrongly, the US president is convinced that the path to success on the domestic front lies in controlling drugs and immigration, as well as bringing industrial production back to US soil.

More controversially, he also seems to harbor expansionist ambitions, including the idea of taking Greenland and potentially Canada “by force” if necessary—a threat taken seriously by Copenhagen and Ottawa. While some of his measures aim to address long-standing domestic issues in the US, they have also caused economic disruptions and geopolitical realignments, forcing both allies and adversaries to reassess their positions in a rapidly changing global landscape.

Seeking New Partnerships

On the other hand, it is possible that while the US’s aggressive actions may scare markets and break traditional alliances, they may also accelerate new forms of investment and cooperation in an increasingly fragmented world. While there are strong incentives for small and medium-sized countries to adopt a more competitive and transactional stance, opportunities for greater solidarity and collaboration also arise, especially in areas such as security, immigration, trade, and climate policies.

Despite the shock caused by the speed and severity of US measures, many countries are quietly adopting deportation agreements for immigrants. Canada, for example, is accelerating efforts to expand its defense spending, reduce its digital and infrastructure dependencies on the US, and even create a civil defense corps. Behind the scenes, virtually all countries (and companies) in the Americas are seeking new partnerships, alliances, and trade agreements with Europe, China, India and the BRICS+ countries.

Regardless of the outcome of these regional coalitions and internal political reforms in the coming years, it is clear that the region as a whole is seeking to reduce its dependence on the US as quickly as possible.

Text translated from the article Intervencionismo dos EUA: As Américas se preparam para o impacto da era Trump 2.0, by Robert Muggah published by The Conversation under the license Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. read the original in: The Conversation.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Pepe Mujica: The Rich Legacy of the Peasant Who Knew How to Make Concessions to the Market Without Losing Ideological Direction

01Pepe Mujica: The Rich Legacy of the Peasant Who Knew How to Make Concessions to the Market Without Losing Ideological Direction -

02Democracy in the Face of Ecological Collapse

02Democracy in the Face of Ecological Collapse -

03New modelling reveals full impact of Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs – with the US hit hardest

03New modelling reveals full impact of Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs – with the US hit hardest -

04New Pope Possesses Attributes That Could Expand Vatican’s Diplomatic Influence in Global Geopolitics

04New Pope Possesses Attributes That Could Expand Vatican’s Diplomatic Influence in Global Geopolitics -

0550 years later, Vietnam’s environment still bears the scars of war – and signals a dark future for Gaza and Ukraine

0550 years later, Vietnam’s environment still bears the scars of war – and signals a dark future for Gaza and Ukraine -

06What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains

06What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains -

07China’s new underwater tool cuts deep, exposing vulnerability of vital network of subsea cables.

07China’s new underwater tool cuts deep, exposing vulnerability of vital network of subsea cables.