Now Reading: Democracy in the Face of Ecological Collapse

-

01

Democracy in the Face of Ecological Collapse

Democracy in the Face of Ecological Collapse

Numerous studies consistently indicate that we have not only surpassed the 1.5°C global warming threshold but are also on a trend to break it and dangerously approach 2°C. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are indeed rising at alarming rates, as highlighted in the 2020 Emissions Gap Report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Given the urgency, achieving meaningful environmental goals can no longer rely on incremental measures. Beyond climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, the gradual reduction of emissions and the phased elimination of fossil fuels require a complete rethinking of our relationship with energy, technology, and natural resource consumption.

The limited progress in reducing GHG emissions is tied to the contemporary economic model, which is central to understanding the factors driving climate change.

Despite scientific consensus, growing public awareness, and civil society mobilization, the actions of democratic governments still seem constrained by a paradigm unable to enact the necessary changes to combat climate change.

The complex relationship between democracy, the environment, and a capitalist model based on classical economic growth presents significant challenges. It even raises the question of whether contemporary democratic institutions and political systems are effective tools for addressing climate change.

The Constraints of Democracy

Certainly, democratic institutions must navigate a plurality of conflicting interests (human rights, markets, industries, natural resource use, etc.) while attempting to address the consequences of climate change.

Moreover, the deliberative mechanisms of democracies—slow, bureaucratic, and subject to pressure from powerful groups, media, or electoral cycles—hinder consensus-building and the implementation of public policies.

While deliberative processes and citizen participation allow for diverse perspectives, they appear too sluggish to enact the urgent reforms needed.

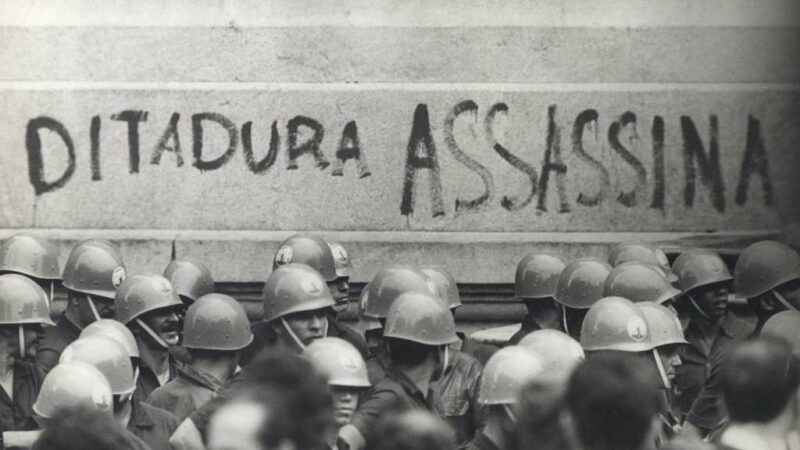

These limitations raise the question of whether democracies are the most suitable instruments for implementing necessary environmental policies. This has sparked debate over whether environmental authoritarianism could be a viable alternative—or even a more effective one—for combating climate change.

In a world where authoritarian governments are increasingly prevalent, it is notable that the last two UN climate conferences were held in regions with weak democratic traditions, such as the United Arab Emirates and Azerbaijan.

Environmental Authoritarianism in China

Within this debate, some studies propose non-participatory, non-democratic models as effective ways to combat climate change. China, the world’s largest consumer of fossil fuel energy, doubling the U.S., is often cited as a leading example of environmental authoritarianism.

The argument is that authoritarian regimes can impose stricter measures more swiftly than democracies. This reasoning suggests that the urgency of climate action may justify suspending—or even eroding—democratic foundations such as the rule of law, social justice, and basic rights and freedoms.

This debate unfolds in a global context where governments openly challenging traditional democratic principles are on the rise. While some authoritarian regimes may implement seemingly successful environmental policies, this approach carries hidden costs, including the erosion of fundamental human rights.

An illustrative example is China’s national campaign to reduce air pollution, where local governments imposed penalties on citizens violating regulations. In places like Linfen Prefecture, the cost of alternatives to coal burning exceeded average incomes, leaving many households without heating in winter under threat of fines.

Such scenarios are more likely in regimes where basic rights and freedoms are unprotected, justified in the name of climate urgency. However, they also legitimize restrictive—even repressive—policies that would be unacceptable in a functioning democracy.

This is not just about technocratic efficiency but about regimes that can enforce decisions through coercion in any domain.

While democratic mechanisms may be slow and their results non-immediate, public debate and participation safeguards prevent authoritarian “solutions” that, though seemingly effective in the short term, have unpredictable consequences.

Debating Climate Emergency Responses

Thus, climate urgency must be addressed through democratic principles not only as a political imperative but also to navigate the ethical dilemmas involved—from uneven geographic impacts to differing responsibilities among corporations, states, and citizens, as well as intergenerational justice.

In any case, environmental authoritarianism, despite its apparent efficiency, threatens democratic values. The erosion of fundamental rights and the absence of public accountability mechanisms are significant concerns.

The response to climate change is not merely a technical issue but a deeply political one, with diverse alternatives and social implications. Different ideological approaches deserve public debate.

Moreover, empirical evidence suggests that, despite their flaws, democratic regimes—even when correlated with economic and technological development—are associated with better environmental initiatives. There is no consensus supporting authoritarian regimes as more effective against climate change. In fact, studies indicate the opposite: democratic political systems offer greater potential for climate action.

Nevertheless, current efforts remain insufficient, and the disruptions caused by climate change—environmental, social, and political—are reshaping governance models.

Democracies must confront these challenges while balancing urgency with mechanisms that uphold democratic values and transform economic imperatives within the framework of planetary sustainability.

Translated text of the article La democracia ante el colapso ecológico, by Zarina Kulaeva published on The Conversation under the license of Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. Read the original in: The Conversation.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

-

01Pepe Mujica: The Rich Legacy of the Peasant Who Knew How to Make Concessions to the Market Without Losing Ideological Direction

01Pepe Mujica: The Rich Legacy of the Peasant Who Knew How to Make Concessions to the Market Without Losing Ideological Direction -

02Democracy in the Face of Ecological Collapse

02Democracy in the Face of Ecological Collapse -

03New modelling reveals full impact of Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs – with the US hit hardest

03New modelling reveals full impact of Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs – with the US hit hardest -

04New Pope Possesses Attributes That Could Expand Vatican’s Diplomatic Influence in Global Geopolitics

04New Pope Possesses Attributes That Could Expand Vatican’s Diplomatic Influence in Global Geopolitics -

05What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains

05What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains -

0650 years later, Vietnam’s environment still bears the scars of war – and signals a dark future for Gaza and Ukraine

0650 years later, Vietnam’s environment still bears the scars of war – and signals a dark future for Gaza and Ukraine -

07China’s new underwater tool cuts deep, exposing vulnerability of vital network of subsea cables.

07China’s new underwater tool cuts deep, exposing vulnerability of vital network of subsea cables.