Now Reading: 40 Years After the End of the Military Dictatorship, Why Does Brazil Still Resist Confronting Its Past?

-

01

40 Years After the End of the Military Dictatorship, Why Does Brazil Still Resist Confronting Its Past?

40 Years After the End of the Military Dictatorship, Why Does Brazil Still Resist Confronting Its Past?

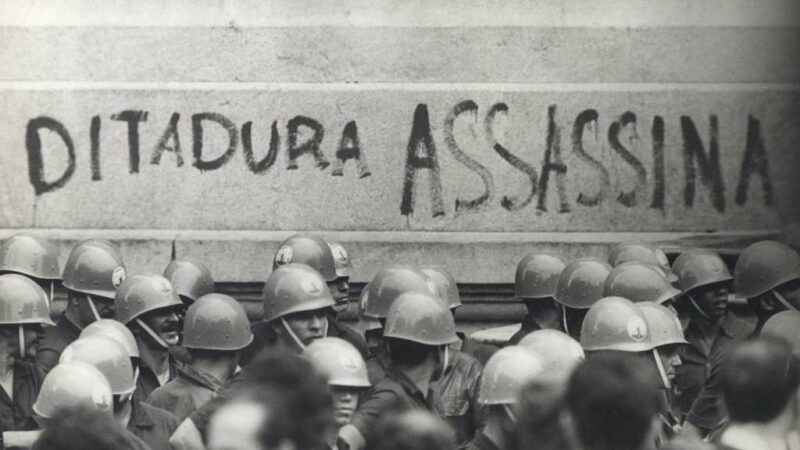

The year marks 40 years since the end of the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964-1985), and with the debate around the period reignited by the success of the film “I Am Still Here” (2024), another issue remains unresolved in the country: the Brazilian state’s debt to the victims of human rights violations committed by the regime.

Despite the implementation of reparations mechanisms, such as the commissions on the Dead and Missing and Amnesty, and the creation of the National Truth Commission, the country still faces challenges in achieving transitional justice.

Moreover, in a context of political polarization and the rise of far-right figures, a survey by the Datafolha Institute released in December indicated that 69% of the Brazilian population currently prefers democracy. Two years ago, the percentage was 79%.

In a 2012 article analyzing the Brazilian case, Fabiana Godinho MacArthur highlighted “mechanisms and strategies” that allowed progress in the country but pointed out an obstacle:

…weighing on the Brazilian transitional process is the preservation of the choice not to hold individual agents of military repression accountable, as well as the denial of any responsibility on their part.

The impunity in the Brazilian case was heavily influenced by the 1979 Amnesty Law, which freed political prisoners and allowed the return of exiles, while also benefiting state agents involved in serious human rights violations, preventing them from being prosecuted. The National Truth Commission’s report listed 377 individuals deemed responsible for crimes during the period.

In an interview with Brasil de Fato, Carla Osmo, a professor at the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp) Law School, noted that Brazil took years to adopt any measures guaranteeing memory, truth, and justice, forcing the families of the dead and missing to seek answers on their own. She also observed:

Regarding criminal accountability, unlike other Latin American countries where the judiciary began applying international human rights norms, allowing prosecutions against state agents for grave human rights violations, in Brazil these actions continued to be blocked. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, especially after the condemnation of the Brazilian state in the Gomes Lund case in 2010, began promoting a series of criminal actions, which now number in the dozens. But these, as a rule, are not accepted by the judiciary, which continues to invoke the Amnesty Law, contrary to international human rights law.

The Gomes Lund case, mentioned by her, refers to the trial against the Brazilian state at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) for violations during the Araguaia Guerrilla. Between 1972 and 1975, the guerrilla movement of militants from the PC do B (Communist Party of Brazil) was suppressed by the regime, resulting in deaths and disappearances without answers.

The Search for Truth

The ruling demanded, among other points, that the country seek the truth about the disappeared, fully compensate the victims, and implement institutional reforms to prevent the repetition of such violations, as well as publicly and unequivocally acknowledge the state’s responsibility.

The Brazilian military dictatorship, which lasted over 20 years, was a period marked by censorship, political persecution, arbitrary arrests, torture, and forced disappearances, used as tools to silence opponents and control society.

The regime also committed other grave abuses, including sexual violence against women, persecution of the Black population and Indigenous peoples, and the suppression of social and cultural movements.

The Institutional Act Number 5 (AI-5), decreed in 1968, marked the peak of repression. With it, torture became an institutionalized practice—accounts from survivors describe the use of methods such as electric shocks, the “pau-de-arara”, and drowning. The vast majority of torturers were never prosecuted.

In 2019, after comments by then-president Jair Bolsonaro (PL, Liberal Party), victims and families submitted a request to the IACHR for the international body to intercede with the Brazilian state to respect the memory and rights of the victims. In 2023, the commission also expressed concern over the closure of the Special Commission on Political Dead and Missing Persons, a decision made at the end of Bolsonaro’s government. It was only reinstated in August 2024 under Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT, Workers’ Party).

When he was still a federal deputy, Bolsonaro was known for his pro-dictatorship positions and for honoring repressors. He even had a poster on his office door mocking the search for the disappeared of Araguaia, with the message, “only dogs look for bones.”

Four Decades Later

With the political reopening in 1985, it was human rights associations and families of the dead and missing who brought visibility to the dictatorship’s crimes and the search for answers. The report “Brazil: Never Again”, compiling data on torture and violations during the period, was published in July of the same year.

The work of these groups was crucial in taking the Brazilian state to international courts, such as the case that led to the IACHR’s condemnation over the Araguaia Guerrilla. The creation of the National Truth Commission was a consequence of this process. The CNV held public hearings and gathered testimonies about human rights violations occurring between 1946 and 1985—the period between Brazil’s last two democratic constitutions, as explained on the commission’s website.

The final report, published in 2014, made 29 recommendations to national authorities, including holding perpetrators of violations accountable, implementing reparations and memory policies, and revising the 1979 Amnesty Law.

At the time, the CNV’s work faced criticism from sectors linked to the military. Months before the report’s completion, for example, in response to a demand from the commission, the Armed Forces denied any misuse of Army, Navy, and Air Force facilities for torture during the regime.

Speaking to Brasil de Fato, Professor Carla Osmo argued that the violations of the period demand a response not only for the victims but for society as a whole. She added:

If what the military dictatorship was, who it affected, and how are not made known, it leaves room for the absurd view that the dictatorship was somehow positive and that its repression was legitimate.

‘Unnatural, Violent Death Caused by the State’

Nearly four decades after the end of the 21-year military dictatorship, in January 2025, notary offices across Brazil began issuing corrected death certificates for victims of repression, stating the true cause of death without requiring legal action.

The move complies with a regulation by the National Council of Justice (CNJ). The cause of death now reads: “unnatural, violent death caused by the state to a disappeared person in the context of systematic persecution of the population identified as political dissidents under the dictatorial regime established in 1964.”

In a report by Jornal Nacional, TV Globo’s news program, former political prisoners Crimeia Almeida and Amélia Teles witnessed the correction of the death certificate of their friend Carlos Nicolau Danielli, a militant of the Communist Party of Brazil, whose death under torture they had witnessed. Teles stated at the time:

The violence he suffered was caused by an authoritarian state, a dictatorial state. It’s written here. This is a matter of justice.

Translated text of the article 40 anos após fim da ditadura militar, por que o Brasil ainda resiste a enfrentar seu passado?, by Laura Chaparro published on Global Voices under the license of Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. Read the original in: Global Voices.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01Pepe Mujica: The Rich Legacy of the Peasant Who Knew How to Make Concessions to the Market Without Losing Ideological Direction

01Pepe Mujica: The Rich Legacy of the Peasant Who Knew How to Make Concessions to the Market Without Losing Ideological Direction -

02Democracy in the Face of Ecological Collapse

02Democracy in the Face of Ecological Collapse -

03New modelling reveals full impact of Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs – with the US hit hardest

03New modelling reveals full impact of Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs – with the US hit hardest -

04New Pope Possesses Attributes That Could Expand Vatican’s Diplomatic Influence in Global Geopolitics

04New Pope Possesses Attributes That Could Expand Vatican’s Diplomatic Influence in Global Geopolitics -

05What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains

05What’s so special about Ukraine’s minerals? A geologist explains -

0650 years later, Vietnam’s environment still bears the scars of war – and signals a dark future for Gaza and Ukraine

0650 years later, Vietnam’s environment still bears the scars of war – and signals a dark future for Gaza and Ukraine -

07China’s new underwater tool cuts deep, exposing vulnerability of vital network of subsea cables.

07China’s new underwater tool cuts deep, exposing vulnerability of vital network of subsea cables.